Friday, August 18, 2006

Thursday, August 17, 2006

More comments re: uplift, personhood, the species barrier and moral consideration

[my responses to a post on the Technoliberation list]:

>"How do you know species barriers are not relevant to moral

>considerations? We have many examples of species, and none of them,

>even dogs, "man's best friend," seems interested in government or

>literature. My view that they should be left alone, unless they enter

>into voluntary relationships with us, comes from what I have learned

>about evolutionary and behavioral biology, not from Star Trek.”

First, the notion that my ethics or perception of animal behaviour is derived from Star Trek is terribly condescending. Such an accusation betrays a bias (and even futureshock) against seemingly futuristic and highly speculative scenarios involving advanced biotechnologies.

Moving on to discuss the merits of the ideas themselves.

Why must we talk about species as a moral limiter? What is so special about a species such that morphological or psychological characteristics are trumped? I know perfectly capable humans who have no interest in government or literature, why do they automatically warrant moral consideration? And what about severely disabled humans who are psychologically incapable of an interest in government or literature, or who have not ‘voluntarily’ entered into relationships? Why do they merit moral consideration where a nonhuman does not? Essentially you want to have your cake and eat it, too; you’re saying that species matter because it comes down to ingrained capability and intent while simultaneously failing to recognize that these capabilities are a) not universal to humans and b) are arguably resident in some nonhumans (eg. Great apes are social creatures who live according to hierarchies (I’d call that gov’t, at least in proto form), and other species, like dolphins and elephants, have shown interest in art).

>No amount of genetic engineering has ever transformed one species into

> another, so they must have acquired discrete, bounded identities over

> the course of evolution.

You’re describing the condition of nonhuman animals, which of course is not an argument. Unless you’re buying into the naturalistic fallacy.

>You perhaps believe that genetic

>manipulation can "uplift" animals to make them more compatible with

>social and cultural practices that are the product of a very specific

>trajectory of human evolution. (The language certainly smacks of

>imperialism and the missionary imperative.)

I wouldn’t say that the goal is to make nonhumans more compatible with social and cultural practices (though there is some efficacy to that). Rather, the whole uplift thought experiment is to determine to the best of our abilities what it is that nonhumans would want for themselves given the availability of uplift technologies, what our moral obligations are to nonhuman animals, and whether or not such a project could ever be safe and effective. You say we run the risk of being imperialistic or evangelical; I say we run the risk of being neglectful to the point of reckless indifference.

>Most likely, such efforts

>will just produce damaged animals, since the relationship between

>genes and traits is complex and context dependent (i.e., the same

>gene, or group of genes, will function very differently in the

>context of the human and pig genomes).

These are open empirical questions. My own personal opinion is that these are not intractable problems.

>Sentient computers -- a

>science fiction fantasy if there ever was one! Is there even a

>glimmer of this in the most powerful supercomputers?

Irrelevant. But telling – you’ve clearly got substrate bias issues.

>Your position

>seems to be a category error: since humans have for too long placed

>other humans in lower or nonequivalent rights categories for

>pernicous reasons such as gender, race, ethnicity, sexual

>orientation, why not just extend the same rights to nonhumans? But

>rights are a human product. We can generalize humane behavior to

>other groups, we can serve our cats vegetarian meals, we can even

>program robots to help rather than harm each other, but that doesn't

>make them members of the primary moral community."

Rights may be a human product, but they apply to all persons—human or otherwise. And your concept of a human monopoly on a ‘primary moral community’ is problematic for reasons already discussed, namely your prejudice against those things we don’t describe as being “human.”

You’re suggesting that we have to leave nonhumans alone because it would be ‘imperalistic’ of us to bring them into civilization and because they have the inability to actually ask to be uplifted. I say it’s an animal welfare issue, that we can assume consent, and that it falls within not just our moral bounds to do so, but within our social obligations seeing as many of these persons already fall within the social contract.

>"How do you know species barriers are not relevant to moral

>considerations? We have many examples of species, and none of them,

>even dogs, "man's best friend," seems interested in government or

>literature. My view that they should be left alone, unless they enter

>into voluntary relationships with us, comes from what I have learned

>about evolutionary and behavioral biology, not from Star Trek.”

First, the notion that my ethics or perception of animal behaviour is derived from Star Trek is terribly condescending. Such an accusation betrays a bias (and even futureshock) against seemingly futuristic and highly speculative scenarios involving advanced biotechnologies.

Moving on to discuss the merits of the ideas themselves.

Why must we talk about species as a moral limiter? What is so special about a species such that morphological or psychological characteristics are trumped? I know perfectly capable humans who have no interest in government or literature, why do they automatically warrant moral consideration? And what about severely disabled humans who are psychologically incapable of an interest in government or literature, or who have not ‘voluntarily’ entered into relationships? Why do they merit moral consideration where a nonhuman does not? Essentially you want to have your cake and eat it, too; you’re saying that species matter because it comes down to ingrained capability and intent while simultaneously failing to recognize that these capabilities are a) not universal to humans and b) are arguably resident in some nonhumans (eg. Great apes are social creatures who live according to hierarchies (I’d call that gov’t, at least in proto form), and other species, like dolphins and elephants, have shown interest in art).

>No amount of genetic engineering has ever transformed one species into

> another, so they must have acquired discrete, bounded identities over

> the course of evolution.

You’re describing the condition of nonhuman animals, which of course is not an argument. Unless you’re buying into the naturalistic fallacy.

>You perhaps believe that genetic

>manipulation can "uplift" animals to make them more compatible with

>social and cultural practices that are the product of a very specific

>trajectory of human evolution. (The language certainly smacks of

>imperialism and the missionary imperative.)

I wouldn’t say that the goal is to make nonhumans more compatible with social and cultural practices (though there is some efficacy to that). Rather, the whole uplift thought experiment is to determine to the best of our abilities what it is that nonhumans would want for themselves given the availability of uplift technologies, what our moral obligations are to nonhuman animals, and whether or not such a project could ever be safe and effective. You say we run the risk of being imperialistic or evangelical; I say we run the risk of being neglectful to the point of reckless indifference.

>Most likely, such efforts

>will just produce damaged animals, since the relationship between

>genes and traits is complex and context dependent (i.e., the same

>gene, or group of genes, will function very differently in the

>context of the human and pig genomes).

These are open empirical questions. My own personal opinion is that these are not intractable problems.

>Sentient computers -- a

>science fiction fantasy if there ever was one! Is there even a

>glimmer of this in the most powerful supercomputers?

Irrelevant. But telling – you’ve clearly got substrate bias issues.

>Your position

>seems to be a category error: since humans have for too long placed

>other humans in lower or nonequivalent rights categories for

>pernicous reasons such as gender, race, ethnicity, sexual

>orientation, why not just extend the same rights to nonhumans? But

>rights are a human product. We can generalize humane behavior to

>other groups, we can serve our cats vegetarian meals, we can even

>program robots to help rather than harm each other, but that doesn't

>make them members of the primary moral community."

Rights may be a human product, but they apply to all persons—human or otherwise. And your concept of a human monopoly on a ‘primary moral community’ is problematic for reasons already discussed, namely your prejudice against those things we don’t describe as being “human.”

You’re suggesting that we have to leave nonhumans alone because it would be ‘imperalistic’ of us to bring them into civilization and because they have the inability to actually ask to be uplifted. I say it’s an animal welfare issue, that we can assume consent, and that it falls within not just our moral bounds to do so, but within our social obligations seeing as many of these persons already fall within the social contract.

More comments re: animal uplift, autism, and enforced neurotypicality

[a response of mine taken from the Technoliberation list]:

> my point: if we invite nonhuman animals to take part in our evolved

> social and democratic processes (and our technological developments),

> will it be understood that we need to respect their own goals for their

> future, particularly if they are able to very clearly indicate that they

> want or don't want a certain modification? Or, will we take the

> position that we know that it's fundamentally good to be able to make

> human speech-sounds, and that obviously Mr. Bonobo shouldn't expect to

> receive his piano lessons unless he agrees to (for crying out loud!) put

> on some PANTS?

There’s no perfect answer to this, mostly because society and medical ethics are not cut-and-dry. As you noted, there are examples already in society where some individuals claim to fall within the bounds of acceptable human functioning while others claim that the same individuals are somehow ‘deficient’ or ‘disabled.’ The autism rights movement (and the disabled rights movement in general) is very much about protecting perceived distinctiveness; a high degree of repugnance is given to efforts in which autistics are forcibly neurotypicalized. The same sort of reaction is experienced by the physically disabled when, for example, an effort is made to ‘cure’ a disability by conforming to the bounds of normal human functioning (e.g. a person without legs should be given artificial legs instead of wheels).

And as you indicated in your post, notions of neurotypicality are normative. Homosexuality was once thought of as a psychological condition and efforts were made in the name of rehabilitation. Western society has a very puritan view of human psychology. It’s one of the reasons why recreational drug use is so chastised. There is a powerful conviction that runs through the West suggesting that altered or alternative psychologies are undesirable and potentially crippling.

So, we’re not doing a great job today recognizing the validity of alternative psychology types, but I have cause for hope. First, a number of movements are afoot that seek to preserve one’s right to their own desired psychology. The Centre of Cognitive Liberty and the Autistic Rights Movements are two examples. I also think that the idea of alternative psychologies will normalized in society, particularly once more powerful neuropharma hits the market.

I think we all need to promote a broader interpretation of neurotypicality, but as we’ve discussed before, not one in which an inbound person’s ability to participate in society is dramatically lessened. It’s unethical for parents to deliberately constrain or predetermine capabilities that will limit their child’s ability to engage in life (or as Rawls would say, invoke inhibitors to the attainment of social justice: “each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive basic liberty compatible with a similar liberty for others.”) Obviously, this is open to huge interpretation, which is why we’re having this conversation. Moreover, an entirely new set of complexities is introduced when a person reaches the age of consent, at which point they (arguably) should have the right to ‘tune out’ in Learyesque fashion. The point, I think, is that a parent can’t impose a Learyesque existence on their child – persons deserve the right to a genetic constitution that will by default maximize their life options rather than constrain them.

In relation to uplift scenarios and animal welfare considerations, there are three things I’ll say to that. First, I agree that uplift must be done respectfully and incrementally with consideration given to advancing the species itself (and its proto-culture) without conforming necessarily to human cognitive and morphological standards. Second, during the course of the process, the input and preferences of the animals themselves must be taken into consideration.

And finally, to second a point that James made earlier, we must acknowledge the fact that as a subject is uplifted, the subject changes. There is no such thing as the immutable self – even outside of uplift scenarios. While continuity of self and existence will be maintained through memory, the precise parameters than make up the animal’s psychology will be in flux. Consequently, the desires and preference of the uplifted subject will change over the course of time. The effect will be akin to a child growing into an adult; we remember our childhood and we maintain certain personality characteristics from our childhood, but we most certainly do not retain our childish personalities and preferences.

Back to the issue of coercion versus consent, I think nonhuman animals who are being uplifted and who wish to preserve their distinct identity and characteristics will have to go about it in the same way humans do today – through the creation of rights movements and by increasing general awareness. That’s how you get people to think outside the box.

> my point: if we invite nonhuman animals to take part in our evolved

> social and democratic processes (and our technological developments),

> will it be understood that we need to respect their own goals for their

> future, particularly if they are able to very clearly indicate that they

> want or don't want a certain modification? Or, will we take the

> position that we know that it's fundamentally good to be able to make

> human speech-sounds, and that obviously Mr. Bonobo shouldn't expect to

> receive his piano lessons unless he agrees to (for crying out loud!) put

> on some PANTS?

There’s no perfect answer to this, mostly because society and medical ethics are not cut-and-dry. As you noted, there are examples already in society where some individuals claim to fall within the bounds of acceptable human functioning while others claim that the same individuals are somehow ‘deficient’ or ‘disabled.’ The autism rights movement (and the disabled rights movement in general) is very much about protecting perceived distinctiveness; a high degree of repugnance is given to efforts in which autistics are forcibly neurotypicalized. The same sort of reaction is experienced by the physically disabled when, for example, an effort is made to ‘cure’ a disability by conforming to the bounds of normal human functioning (e.g. a person without legs should be given artificial legs instead of wheels).

And as you indicated in your post, notions of neurotypicality are normative. Homosexuality was once thought of as a psychological condition and efforts were made in the name of rehabilitation. Western society has a very puritan view of human psychology. It’s one of the reasons why recreational drug use is so chastised. There is a powerful conviction that runs through the West suggesting that altered or alternative psychologies are undesirable and potentially crippling.

So, we’re not doing a great job today recognizing the validity of alternative psychology types, but I have cause for hope. First, a number of movements are afoot that seek to preserve one’s right to their own desired psychology. The Centre of Cognitive Liberty and the Autistic Rights Movements are two examples. I also think that the idea of alternative psychologies will normalized in society, particularly once more powerful neuropharma hits the market.

I think we all need to promote a broader interpretation of neurotypicality, but as we’ve discussed before, not one in which an inbound person’s ability to participate in society is dramatically lessened. It’s unethical for parents to deliberately constrain or predetermine capabilities that will limit their child’s ability to engage in life (or as Rawls would say, invoke inhibitors to the attainment of social justice: “each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive basic liberty compatible with a similar liberty for others.”) Obviously, this is open to huge interpretation, which is why we’re having this conversation. Moreover, an entirely new set of complexities is introduced when a person reaches the age of consent, at which point they (arguably) should have the right to ‘tune out’ in Learyesque fashion. The point, I think, is that a parent can’t impose a Learyesque existence on their child – persons deserve the right to a genetic constitution that will by default maximize their life options rather than constrain them.

In relation to uplift scenarios and animal welfare considerations, there are three things I’ll say to that. First, I agree that uplift must be done respectfully and incrementally with consideration given to advancing the species itself (and its proto-culture) without conforming necessarily to human cognitive and morphological standards. Second, during the course of the process, the input and preferences of the animals themselves must be taken into consideration.

And finally, to second a point that James made earlier, we must acknowledge the fact that as a subject is uplifted, the subject changes. There is no such thing as the immutable self – even outside of uplift scenarios. While continuity of self and existence will be maintained through memory, the precise parameters than make up the animal’s psychology will be in flux. Consequently, the desires and preference of the uplifted subject will change over the course of time. The effect will be akin to a child growing into an adult; we remember our childhood and we maintain certain personality characteristics from our childhood, but we most certainly do not retain our childish personalities and preferences.

Back to the issue of coercion versus consent, I think nonhuman animals who are being uplifted and who wish to preserve their distinct identity and characteristics will have to go about it in the same way humans do today – through the creation of rights movements and by increasing general awareness. That’s how you get people to think outside the box.

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

SETI and the human craving for uplift

I just finished reading a rather weak and unconvincing critique of SETI by Peter Schenkel over at the Skeptical Inquiry site. It contains the usual errors: an over emphasis on the Rare Earth Hypothesis, far too many sociological considerations that couldn’t possibly be exclusive to all intelligent life, and no thought given to the existential mode of postbiological intelligences (including the presence of megaprojects, both structural and computational).

I just finished reading a rather weak and unconvincing critique of SETI by Peter Schenkel over at the Skeptical Inquiry site. It contains the usual errors: an over emphasis on the Rare Earth Hypothesis, far too many sociological considerations that couldn’t possibly be exclusive to all intelligent life, and no thought given to the existential mode of postbiological intelligences (including the presence of megaprojects, both structural and computational). Anyway, Schenkel made a comment that got me thinking about SETI and what contact means from the perspective of human desires. He noted that,

I would be the first one to react to such a contact event with great delight and satisfaction. The knowledge that we are not alone in the vast realm of the cosmos, and that it will be possible to establish a fruitful dialogue with other, possibly more advanced intelligent beings would mark the biggest event in human history. It would open the door to fantastic perspectives.This is a sentiment that I believe is commonly shared among the contact optimists and those often think about the SETI endeavor. Contact, it is largely assumed, would have a paradigmatic effect on human civilization. Over the years I've heard these sorts of comments: Humans would be humbled and brought together in a state of pan-universal loving kindness. Religions and sectarianism would become irrelevant overnight. We would be able to acquire radically advanced technologies and transform our civilization and species. Humans would have the opportunity to adopt ETI values and social institutions that would undoubtedly be superior to our own.

In other words, we want to be uplifted.

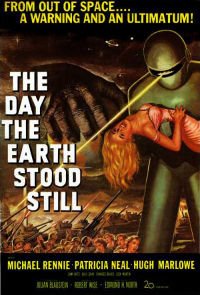

Science fiction has addressed this issue a number of times (of course). In the classic 50’s film The Day the Earth Stood Still, audiences, who were still shell-shocked from WWII and coming to grips with the presence of apocalyptic technologies, watched as extraterrestrials came down from the heavens and set things straight (talk about wish fulfillment). Essentially, ETI’s established a robotic police presence on Earth to keep potentially combative nation-states in line.

Science fiction has addressed this issue a number of times (of course). In the classic 50’s film The Day the Earth Stood Still, audiences, who were still shell-shocked from WWII and coming to grips with the presence of apocalyptic technologies, watched as extraterrestrials came down from the heavens and set things straight (talk about wish fulfillment). Essentially, ETI’s established a robotic police presence on Earth to keep potentially combative nation-states in line. Similar themes are explored in ET: The Extra Terrestrial, Starman and K-PAX in which enlightened aliens exposed the backwardness and maliciousness of humanity. They may have not set us straight in these movies, but they caused us to be introspective at the very least.

And in David Brin’s Uplift series, an advanced species of extraterrestrials make it their business to traverse the Galaxy uplifting sentient creatures of all sorts, bringing them into a more advanced and dignified state of being. The same sort of thing is explored in Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001 in which an advanced intelligence instigates the rapid makeover of humanity as illustrated by David Bowman’s transformation into the Star Child.

Some socio-cultural groups have converted these sorts of ideas into religious-like expectations. The most prominent of these are the Raelians, who not only believe that human life was spawned by advanced ETI’s, but that they will eventually return to save humanity and bring eternal life. This is essentially a messianic-style religion that has taken root in the 21st century, and it reveals some very interesting aspects about human nature and religiosity as it manifests in culture. I could say more about UFOlogists, but perhaps I’ll save that rant for another post.

Some socio-cultural groups have converted these sorts of ideas into religious-like expectations. The most prominent of these are the Raelians, who not only believe that human life was spawned by advanced ETI’s, but that they will eventually return to save humanity and bring eternal life. This is essentially a messianic-style religion that has taken root in the 21st century, and it reveals some very interesting aspects about human nature and religiosity as it manifests in culture. I could say more about UFOlogists, but perhaps I’ll save that rant for another post. These examples, both science fictional and social, are representative of the human desire for both cultural and biological uplift. It’s generally assumed that because we can’t fix ourselves that ETI’s will do it for us. Moreover, with ETI’s and their radically advanced technology and enlightened natures, the potential for extreme existential transformation is non-trivial to say the least.

Which leads to the final point I’d like to make, and that’s in regards to the issue of animal uplift. I have to wonder, if there is such a thing as the human desire to be uplifted, why would we assume that nonhumans wouldn’t also desire to be uplifted?

Or are humans the only exalted species who deserve this honor? If and when the ETI’s come, will we tell them to ignore nonhumans? I wonder how the ETI’s would react to that. Perhaps they’ll leave humans alone and uplift their dolphin friends just to spite us over our stupidity.

Thanks for all the fish, you speciesist morons!

Aubrey interviewed on CBC's Canada Now (Feb 2006)

Aubrey de Grey interviewed on CBC's Canada Now. This was posted on YouTube back in February of 2006 -- not quite sure when it actually aired. As per usual, Aubrey's answers are well thought out and tactful.

Monday, August 14, 2006

More on animal uplift ethics

Here's my response to a recent (anonymous) posting on the Technoliberation list (I'm responding to the inset paragraphs):

> "One can recognize the "right" (a human-

> granted right) of sentient beings not to be killed, tortured and

> eaten, and the immorality (based, again, on human-generated moral

> standards) of keeping in captivity primates, cetaceans, cephalopods,

> etc., without imagining that they would want to participate in "our"

> democratic processes, religious practices, etc. It seems this latter

> sentiment is just a form of imperialistic paternalism.

Well, I'd like to think that "human-generated moral standards," which is a massive work in progress and has been steadily refined for the past 4-5 thousand years, has both objective and universal value. I strongly believe that uplifted nonhumans will want to tap into our collective body of knowledge and adapt certain moral codes as they see fit. Denying them this and/or having them reject this would be quite bizarre (and unexpected as far as I'm concerned).

Now, as for uplifted nonhumans potentially not wanting to participate in "our" democratic processes, religions, etc., that's a bit more complicated. My future vision sees an inter-species society represented by multi-cultural, multi-national, multi-religious, and multi-species groups. The idea of socially stratifying society even further based on species grounds seems somewhat anathematic to the whole thrust of history and the entire point of bringing nonhuman persons into technological and social modernity.

I'm not suggesting that nonhumans be coerced into joining human institutions. There are precedents already in some countries where distinct societies can seek social isolation (to a degree) within a larger nation state (e.g. the Amish & Mennonites, certain aboriginal groups, etc.). What I do believe, however, is that uplifted nonhumans should at the very least be encouraged to represent themselves within a larger democratic inter-species politic. But I think this is largely moot as they'll likely decide this of their own volition.

Which brings me to the next point: this isn't for us to decide -- it'll be up to them. If they want to join human society, and we don't allow them in, that would be a blatant instance of apartheid.

By the way, your term "imperialistic paternalism" is strikingly reactionary and very loaded. No one is talking about exploiting nonhumans and I don't think such a project should be considered patronizing. The impetus behind a potential animal uplift project should be compassion tied in with a sense of moral responsibility and stewardship. Moreover it's time to acknowledge that many nonhumans are already persons in their own right and should already be included in the social contract. We're currently playing catch-up with our moral obligations, but human speciesism is an obstacle that's hard to overcome.

As James mentioned earlier, we've got to stop creating these false dichotomies that separate human people from nonhuman people. Once we get over the species barrier and look upon these nonhumans as people in their own right, then we can start to construct some serious dialogue about how we should go about bringing them out of Darwinian jungle existence and into civilization--something to which I personally ascribe great value and moral worth.

> And just

> because some irresponsible humans can get credit cards or are given

> access to distilled spirits doesn't mean we should make these

> available to bonobos who indicate they like to get drunk or play

> with consumer goods. If these practices arise from their own

> societies, that's a different story.

Again, you're describing an "us and them" scenario. Just which practices and accoutrements, exactly, should we prohibit nonhumans from having and how could we ever reach consensus on this? Now *that's* paternalistic! It's an absurd suggestion--they should only be allowed to possess those "practices [that] arise from their own societies"? Spare me. It's not as if they would exist in a vacuum outside of mainstream society. Further, if we shouldn't give them our booze and credit cards, what about other things like medicine and fresh food? What about access to doctors and social safety nets? What about allowing inter-species relationships and work environments? Or are you suggesting that uplifted animals endowed with the cognitive capacity of a human would rather live an Amish like life in the deep jungle? I hardly think so.

> Concerning demotion from

> personhood, human societies are still at the beginning of dealing

> with who's in and who's out with respect to civil rights.

Nonsense. We're nearly at the tail-end of this process and about to embark on the most profound project yet: widening the social and moral circle to include nonhuman people.

> A great

> ape has more claim on rights than a brain-dead human, or than an

> organism whose brain is half-human half-rat. But the right of the

> ape is primarily the right to be left alone by humans. The rights of

> chimeras or genetically-deranged clones would be the right not to

> have further cruelties visited upon them consequent on iatrogenic

> physical and social dislocations -- that is the right to be life-

> long wards of their creators or owners."

You're describing negative rights, some of which are valid (like privacy). What about the right to a healthy body and mind? Or the right to participate as a full and equal member in the wider politic? It's interesting that this is brought up now because Sue Savage-Rumbaugh (an expert in bonobo language capacity) presented a lecture today in which she claims she has recorded the desires of bonobos. The list reads as follows:

1. A recognition of their level of linguistic competency and ability to self-determine and self-express through language by the humans who keep them in captivity

1. To travel from place to place

2. To obtain their own sustenance

3. To plan ways of maximizing travel and resource procurement

4. To transmit their cultural knowledge to their offspring

5. To be apart from others for periods of time

6. To develop and fulfill a unique role in the group

7. For the group to split apart and to come together to share information regarding distal locations

8. To maintain life-long contact with individuals whom they love

9. To go to new places they have never been before

10. To live free from fear of human beings attacking them

11. To have food that is fresh and of their choice

12. To experience the judgment of their peers regarding their capacity to appropriately carry out their role in the social group, on behalf of

the good of the group

Now, if this is what an unaugmented bonobo person can articulate today, imagine the greater insight that more advanced cultural and biological uplift will reveal.

Essentially, it's time to stop fixating on what humans think nonhuman persons need and actually take into consideration what they themselves would prer. Sure, we can get all perverse and cynical and mock human artifacts like "booze" and credit cards -- but you know what, I love a glass of cabernet and thank goodness I can finance my upcoming vacation on a piece of plastic. And why wouldn't a nonhuman person come to the same conclusion. Moreover, why shouldn't we let them come to the same conclusion?

Cheers,

George

> "One can recognize the "right" (a human-

> granted right) of sentient beings not to be killed, tortured and

> eaten, and the immorality (based, again, on human-generated moral

> standards) of keeping in captivity primates, cetaceans, cephalopods,

> etc., without imagining that they would want to participate in "our"

> democratic processes, religious practices, etc. It seems this latter

> sentiment is just a form of imperialistic paternalism.

Well, I'd like to think that "human-generated moral standards," which is a massive work in progress and has been steadily refined for the past 4-5 thousand years, has both objective and universal value. I strongly believe that uplifted nonhumans will want to tap into our collective body of knowledge and adapt certain moral codes as they see fit. Denying them this and/or having them reject this would be quite bizarre (and unexpected as far as I'm concerned).

Now, as for uplifted nonhumans potentially not wanting to participate in "our" democratic processes, religions, etc., that's a bit more complicated. My future vision sees an inter-species society represented by multi-cultural, multi-national, multi-religious, and multi-species groups. The idea of socially stratifying society even further based on species grounds seems somewhat anathematic to the whole thrust of history and the entire point of bringing nonhuman persons into technological and social modernity.

I'm not suggesting that nonhumans be coerced into joining human institutions. There are precedents already in some countries where distinct societies can seek social isolation (to a degree) within a larger nation state (e.g. the Amish & Mennonites, certain aboriginal groups, etc.). What I do believe, however, is that uplifted nonhumans should at the very least be encouraged to represent themselves within a larger democratic inter-species politic. But I think this is largely moot as they'll likely decide this of their own volition.

Which brings me to the next point: this isn't for us to decide -- it'll be up to them. If they want to join human society, and we don't allow them in, that would be a blatant instance of apartheid.

By the way, your term "imperialistic paternalism" is strikingly reactionary and very loaded. No one is talking about exploiting nonhumans and I don't think such a project should be considered patronizing. The impetus behind a potential animal uplift project should be compassion tied in with a sense of moral responsibility and stewardship. Moreover it's time to acknowledge that many nonhumans are already persons in their own right and should already be included in the social contract. We're currently playing catch-up with our moral obligations, but human speciesism is an obstacle that's hard to overcome.

As James mentioned earlier, we've got to stop creating these false dichotomies that separate human people from nonhuman people. Once we get over the species barrier and look upon these nonhumans as people in their own right, then we can start to construct some serious dialogue about how we should go about bringing them out of Darwinian jungle existence and into civilization--something to which I personally ascribe great value and moral worth.

> And just

> because some irresponsible humans can get credit cards or are given

> access to distilled spirits doesn't mean we should make these

> available to bonobos who indicate they like to get drunk or play

> with consumer goods. If these practices arise from their own

> societies, that's a different story.

Again, you're describing an "us and them" scenario. Just which practices and accoutrements, exactly, should we prohibit nonhumans from having and how could we ever reach consensus on this? Now *that's* paternalistic! It's an absurd suggestion--they should only be allowed to possess those "practices [that] arise from their own societies"? Spare me. It's not as if they would exist in a vacuum outside of mainstream society. Further, if we shouldn't give them our booze and credit cards, what about other things like medicine and fresh food? What about access to doctors and social safety nets? What about allowing inter-species relationships and work environments? Or are you suggesting that uplifted animals endowed with the cognitive capacity of a human would rather live an Amish like life in the deep jungle? I hardly think so.

> Concerning demotion from

> personhood, human societies are still at the beginning of dealing

> with who's in and who's out with respect to civil rights.

Nonsense. We're nearly at the tail-end of this process and about to embark on the most profound project yet: widening the social and moral circle to include nonhuman people.

> A great

> ape has more claim on rights than a brain-dead human, or than an

> organism whose brain is half-human half-rat. But the right of the

> ape is primarily the right to be left alone by humans. The rights of

> chimeras or genetically-deranged clones would be the right not to

> have further cruelties visited upon them consequent on iatrogenic

> physical and social dislocations -- that is the right to be life-

> long wards of their creators or owners."

You're describing negative rights, some of which are valid (like privacy). What about the right to a healthy body and mind? Or the right to participate as a full and equal member in the wider politic? It's interesting that this is brought up now because Sue Savage-Rumbaugh (an expert in bonobo language capacity) presented a lecture today in which she claims she has recorded the desires of bonobos. The list reads as follows:

1. A recognition of their level of linguistic competency and ability to self-determine and self-express through language by the humans who keep them in captivity

1. To travel from place to place

2. To obtain their own sustenance

3. To plan ways of maximizing travel and resource procurement

4. To transmit their cultural knowledge to their offspring

5. To be apart from others for periods of time

6. To develop and fulfill a unique role in the group

7. For the group to split apart and to come together to share information regarding distal locations

8. To maintain life-long contact with individuals whom they love

9. To go to new places they have never been before

10. To live free from fear of human beings attacking them

11. To have food that is fresh and of their choice

12. To experience the judgment of their peers regarding their capacity to appropriately carry out their role in the social group, on behalf of

the good of the group

Now, if this is what an unaugmented bonobo person can articulate today, imagine the greater insight that more advanced cultural and biological uplift will reveal.

Essentially, it's time to stop fixating on what humans think nonhuman persons need and actually take into consideration what they themselves would prer. Sure, we can get all perverse and cynical and mock human artifacts like "booze" and credit cards -- but you know what, I love a glass of cabernet and thank goodness I can finance my upcoming vacation on a piece of plastic. And why wouldn't a nonhuman person come to the same conclusion. Moreover, why shouldn't we let them come to the same conclusion?

Cheers,

George

Sunday, August 13, 2006

Sue Savage-Rumbaugh on the welfare of apes in captivity

Tomorrow, on August 14, Dr. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh will be giving a presentation about the welfare of apes in captivity at a conference oraganized by the Animal Behavior Society. Savage-Rumbaugh, who is a lead scientist at the Great Ape Trust of Iowa (a world-class research center dedicated to studying the behavior and intelligence of great apes), is the first and only scientist doing language research with bonobos.

Tomorrow, on August 14, Dr. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh will be giving a presentation about the welfare of apes in captivity at a conference oraganized by the Animal Behavior Society. Savage-Rumbaugh, who is a lead scientist at the Great Ape Trust of Iowa (a world-class research center dedicated to studying the behavior and intelligence of great apes), is the first and only scientist doing language research with bonobos.I recently cited her work in my animal uplift paper, "All Together Now", noting how the Great Ape Trust was not merely an excellent example of cultural uplift in nonhuman animals, but also a viable model for future institutions that may engage in more advanced uplift projects. As I stated in the paper: "...the Great Ape Trust model is an excellent starting block for not just cultural uplift, but for biological uplift as well. This endeavor is not meant to assimilate or “humanize” nonhuman species, but instead efforts that work to advance apes and their proto-culture. In this way, bonobos and other potentially uplifted nonhumans will ideally become autonomous decision making agents within a larger inter-species society. As the organizers of the Trust themselves state, the apes’ intelligence, communication, social interactions and cultural expression must be advanced respectfully, honorably and openly."

Dr. Savage-Rumbaugh was kind enough to send me an advance copy of her ABS ape welfare presentation, which is titled "Welfare of Apes in Captive Environments: Comments on, and by, a Specific Group of Apes." Her thesis takes a look at a very important issue that pertains directly to the problem of human and nonhuman social and cultural stratification. And as the title suggests, she will be presenting material on behalf of the great apes themselves.

Specifically, Savage-Rumbaugh argues that zoo and other ape confinement administrators, despite their best intentions to create idyllic environments for apes in captivity, have in reality created the illusion of appropriate care. "It is a manufactured 'happy ape world' based on a false dichotomy between ourselves and apes," she writes, "It is like something akin to saying that a human prison be a wonderful place if we would but provide prisoners with bedspreads, televisions, and beer." These illusions, she argues, "are constructed by our peculiarly scientifically informed western view of what apes ought to be, rather than what they might have the potential to be." Moreover, these are illusions we wish to see, she says, because they cover "more difficult and deeper truths." What she is alluding to is the rampant speciesism that runs through Western society and the fear and confusion about what we should actually be doing about ape socialization and inclusion.

What zoo administrators have done in recent years to improve captive welfare in apes is focus on the need for social companions, adequate cage space, fresh fruits and vegetables, variety in the diet, and some type of 'enrichment' (i.e. the opportunity for apes to provision or forage for food). Efforts like these are attempts to mimic what the apes would encounter in their natural environment. Quite obviously these measures are vastly superior to small and sterile cages, but what Savage-Rumbaugh argues is that these new models make the 'visual aspect' of the bonobos environment more entertaining and acceptable to the viewer, namely visitors to the zoo and the administrators themselves. What is not happening, however, is taking into consideration what the apes themselves would prefer.

At the core of Savage-Rumbaugh's work is the conviction that these preferences can in fact be assessed. What she has uncovered in her decades of work studying the language capacities of the bonobo people is the profoundly powerful way in which they can comprehend and apply language (for an example of how she works, watch this video). Essentially, Savage-Rumbaugh claims we can simply ask the apes themselves what it is they want and need.

And this is exactly what she has done, and this is precisely what she intends to show at the ABS conference on August 14. Based on her questioning of the bonobos, here is a list of a dozen things that the bonobos claim to desire for themselves:

1. A recognition of their level of linguistic competency and ability to self-determine and self-express through language by the humans who keep them in captivityAcknowledging the inevitable disbelief and hostility that will confront her findings, Savage-Rumbaugh says, "I did not invent these items on my own." She writes,

1. To travel from place to place

2. To obtain their own sustenance

3. To plan ways of maximizing travel and resource procurement

4. To transmit their cultural knowledge to their offspring

5. To be apart from others for periods of time

6. To develop and fulfill a unique role in the group

7. For the group to split apart and to come together to share information regarding distal locations

8. To maintain life-long contact with individuals whom they love.

9. To go to new places they have never been before

10. To live free from fear of human beings attacking them

11. To have food that is fresh and of their choice.

12. To experience the judgment of their peers regarding their capacity to appropriately carry out their role in the social group, on behalf of the good of the group

These items represent a distillation of specific kinds of things that these bonobos have requested repeatedly across the 4 decades of research with them. When these requests are met, to the degree that I have been able to do so, new and unexpected competencies have emerged in this group. Many of these competencies remain to be documented in sufficient detail. Keeping up with their emergence has proven to require a full-time effort in and of itself. Providing bonobos with these kinds of opportunities has not fit comfortably within the standing cultural views of what one ought to do for apes and thus has constantly resulted cultural clashes which express themselves in reviews of submitted articles, reviews by groups ostensibly trying to protect animals (by keeping them extremely restrained), by funding agencies, by state and federal requirements and by peers. The need to design and maintain a proper environment for these bonobos has become an all consuming task, because our culture beliefs are not structured to accord them the kind of world they require.The real issue, she says, is not ‘What are they like and how should we treat them?’ The real issue is ‘What do we want to permit them to become?’

I applaud the work of Dr. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh and the Great Ape Trust who I believe are doing remarkable and truly progressive work on behalf of all the great apes.

Tags: animal uplift, bioethics, animal rights, personhood, cultural uplift, animal welfare, great ape trust, great apes, sue savage-rumbaugh.

Cryonics Society of Canada potluck dinner, 2006

This past Saturday August 12 was the Cryonics Society of Canada's annual potluck dinner. Allan Randall, the director of CSC, was kind enough to organize and host the event.

This past Saturday August 12 was the Cryonics Society of Canada's annual potluck dinner. Allan Randall, the director of CSC, was kind enough to organize and host the event. This was my first time attending a CSC event (I don't have a cryonics contract, but I'm an avid supporter of the cause). The Toronto Transhumanist Association and the CSC have worked together to support each other over the years.

This year the CSC was fortunate to have the Cryonic Institute's Ben Best give a presentation.

I don't think Ben was taking his audience into consideration when he gave his talk; he gave a broad overview of cryonics and talked about his recent battles with neysayers. I think the crowd was hoping for some more technical information and cutting edge inside news into the cryonics and cryogenics industry.

I don't think Ben was taking his audience into consideration when he gave his talk; he gave a broad overview of cryonics and talked about his recent battles with neysayers. I think the crowd was hoping for some more technical information and cutting edge inside news into the cryonics and cryogenics industry.The potluck and lecture was held outdoors and it was hotter than hell. With the midday sun pounding down on us, it was somewhat surreal and out of context to be talking about freezing bodies at extremely low temperatures. Over the course of Ben's talk, a number of us migrated to the far back to find shelter in the shade.

I took some photographs during the event, including some of Ben's posters. Click here to see the slideshow.

I took some photographs during the event, including some of Ben's posters. Click here to see the slideshow.

Saturday, August 12, 2006

Islamic fascism? Actually, yes.

George W. Bush has caused quite a row with his recent ‘Islamic fascism’ remark. The neo-cons are quite obviously establishing the ideological parameters within which they are continuing their propaganda campaign and maintaining the American public’s high level of agitation and fear. In the process, Bush has grossly over-simplified both the nature of current geopolitics and the religion of Islam itself. Quite justifiably, a number of Muslims are quite upset with Bush’s rather sweeping and inconsiderate remarks.

George W. Bush has caused quite a row with his recent ‘Islamic fascism’ remark. The neo-cons are quite obviously establishing the ideological parameters within which they are continuing their propaganda campaign and maintaining the American public’s high level of agitation and fear. In the process, Bush has grossly over-simplified both the nature of current geopolitics and the religion of Islam itself. Quite justifiably, a number of Muslims are quite upset with Bush’s rather sweeping and inconsiderate remarks. That said, there are some underlying truths to the characterization of radical Islam as a fascistic ideology (again, I take great pains to distinguish between Islamic fundamentalism and the more commonly recognized benign and mainstream variant of Islam). The rise of fanatical theocracies (Ahmadinejad’s Iran) and extremist non-state actors (al-Qaeda) have the indelible marks of far-right totalitarian politics.

And I’m hardly alone on this one. Earlier this year, for example, a number of prominent intellectuals published a statement in condemnation of what they regarded as the rise of Islamic totalitarianism. The list of thinkers who signed this statement included Salmon Rushdie, French philosopher Bernard Henri-Levy and exiled Bangladeshi writer Taslima Nasreen. In the statement, they wrote that "After having overcome fascism, Nazism and Stalinism, the world now faces a new global threat: Islamism…We, writers, journalists, intellectuals, call for resistance to religious totalitarianism and for the promotion of freedom, equal opportunity and secular values for all."

Rushdie et al are correct in their assertion that radical Islam has the characteristics of a totalitarian ideology, but I believe they have understated its fascistic elements.

Many people have the idea that fascism is the monopoly of white supremacist types. This is not the case. At its core, fascism describes the rise of a self-identified group that has grossly exaggerated its historical and societal significance. This self-identity, which typically manifests as a sense of superiority or shared destiny, can encompass anything from race, nationhood, religion, and a shared cultural heritage.

As historian Allan Cassels noted in his book, Fascism, virtually every nation has what is referred to a pre-fascist culture. For the early 20th century Germans, they identified with their race, the volk, and their mythical 'glorious' past. At the same time, many other European nations experimented with fascism, including Italy, Spain, England and even the United States.

Today, this pre-fascist culture is weak in liberal society, but it is rearing its ugly head in some of the Islamic nations. Al-Qaeda, for example, is a paramilitary organization with the stated task of reducing the outside influence of Islamic affairs. This is very much an example of cultural xenophobia and an overstated sense of social mission. Like the fascists of 20th century Europe who feared the specter of Bolshevik globalization, many Muslims today fear the encroachment of American and Jewish values. The result is a far-right, exclusionary, militaristic, and hyper-sensitive counter-reaction in the form of fascism.

Which leads to the next indelible characteristic of fascism: a common enemy. The racist Nazis rallied the nation to deal with what they considered to be the Jewish problem. The Jews were an identifiable enemy who could be blamed for all the problems of the state. They also targeted the Bolsheviks, whose extreme left position polarized and radicalized the right even further. Today, the Jews have once again been targeted by a far-right group, this time in the Mid East—but now they have been joined by the Americans (whose capitalist imperialism and social liberalism has taken the place of communism).

Other characteristics of fascism include a charismatic and populist leader, which Iran quite clearly has in President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. What’s particularly frightening is that Ahmadinejad clearly believes his own hype. He is not so much a dictator as he is an ideologue.

By hype I mean ideology--or in this case, theological ideology. And in this sense Islamic totalitarianism is distinguished from the more secular or socialistic forms of totalitarianism. Where Marxism and fascism had ideologies informed by political, philosophical, and even (pseudo)scientific texts, radical Islam is a theocratic framework that draws its authority from religious sources.

It’s a fine point, but it’s worth mentioning. Islamic totalitarianism, while arguably far-right, is an ideological horse of a different colour. What it shares with more traditional notions of totalitarianism, however, is that is that the source of authority does not come from one individual or group of individuals (i.e. authoritarianism), but instead emanates from a monopolistic ideological framework that is enforced as the only true law of the land.

Indeed, democracy, due process and other elements of social justice as we know it in liberal democracies are absent in countries like Iran and the former Taliban Afghanistan. The goal of these theocracies is to embed religious ideology across the land and to maintain a monopoly on all ideas and institutions; radical Islam, like any totalitarian ideology, is enforced as the alpha and omega of personal existence (the state regulates nearly every aspect of public and private behavior). In this sense the revolution that is Islamic totalitarianism is comparable to the Stalinization of the Soviet Union and the work of the Nazis in 1930’s Germany. The Soviets tried to create a worker's utopia and the New Man, while the Nazis worked to ensure racial purity and create a 1,000 year Reich; Islamic fundamentalists want to create a heaven on earth – a phenomenon comparable to the quasi-totalitarian and theocratic efforts of the Calvinists in 16th century Geneva.

As for the Islamic revolution, one example that will forever stand out in my mind is when the Taliban destroyed Afghanistan’s Buddhist statues. This was an explicitly revolutionary act against those ideas and institutions that potentially rivaled the tenants of the ruling ideology; all revolutions seek to destroy the past, and this one is no different. Another example of zero tolerance toward opposing viewpoints was the recent row over the caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed in the Danish daily newspaper Jyllands-Posten. Western notions of free expression and the free press are lost on the theologues.

So, while Bush and the neo-cons wage their obverse Christian crusade against the ‘Islamic fascists’, they have (likely unintentionally) revealed a disturbing aspect of extremist politics in the Middle East. And as each side continues to antagonize each other, modern politics migrates further and further into the extreme fringes.

Tags: islamic fascism, islamic totalitarianism, fascism, islamic fundamentalism, politics, totalitarianism.

When do uplifted nonhumans become citizens?

[this post is a copy of my response to question recently posted on the Technoliberation list]:

> A colleague of mine asks: "I understand personhood theory to include

> animals, or at least "uplifted" animals. Who decides when they have

> been uplifted enough to gain the right to vote, drink alcoholic

> beverages, or apply for credit? If not every "citizen" is equal, then

> the degree of chimerism of a chimera, for example, or genetic

> concordance with some agreed on standard in a genetically engineered

> ape, or genetically mis-engineered human, may lead to "demotion" as

> well as uplifing with respect to civil rights and liberties."

The first thing to ask is how human society goes about this. Your first question is "who decides?" Well, who decides in human society that humans can vote, drink booze, and apply for credit?

The state declares that if you're a citizen and you've reached the age of consent, you can vote. That's a pretty liberal and sweeping allowance. There's a general assumption of personhood; other factors, like level of education, race, gender, sexual orientation, etc., are irrelevant. So, when it comes to uplifted animals, citizenship and the right to vote can't be tied into their "species," or other superfluous characteristics that we ourselves don't invoke as reasons for not allowing a person to vote.

Regarding the booze question, again that's the state deciding in conjunction with democratically achieved consensus and a dash of social contract thrown in. And as for applying for credit, that's quite obviously up to the individual companies who are offering it. Based on what I've seen to date in terms of how credit cards are given out like candy, I'm surprised that credit card companies haven't already offered credit to bonobos and platypuses.

Your next question is about the equality of citizens. Actually, once the age of consent is achieved (and you haven't violated the social contract with anti-social behaviour), you are equal under the law regardless of your physical and psychological proclivities. We don't have tiers of citizenship in liberal democracies -- to do so would be a form of apartheid. I think it would be an extremely bad idea to start "demoting" uplifted nonhumans or psychological delayed humans based on some personhood metric. It's a binary concept - you're either an equal citizen under the law or you're not a citizen.

Ultimately, I think your question is this: at what point does an uplifted nonhuman enter the social contract? I would argue that once personhood is determined in an animal, the social contract comes into play. We cannot discriminate between animal and human societies. Nonhumans today already deserve state protection and laws to defend their interests (ergo the pending progressive citizenship legislation in Spain that would recognize the great apes) -- even though they cannot articulate their needs themselves. It's obvious when abuse happens, and it's our responsibility to look out for nonhuman interests. They are part of the social contract, but we acknowledge that their limited psychologies don't allow for other citizenship type behaviour like voting. The same policy is applied to small children and the severely disabled. There is nothing new here.

As for voting and other citizenship perks, we'll know that uplifted animals want to participate in the social and political arena when they start asking for it -- and we'll have to listen. To ignore their pleas for political inclusion, the right to vote and organize, would be discrimination and unconstitutional.

> A colleague of mine asks: "I understand personhood theory to include

> animals, or at least "uplifted" animals. Who decides when they have

> been uplifted enough to gain the right to vote, drink alcoholic

> beverages, or apply for credit? If not every "citizen" is equal, then

> the degree of chimerism of a chimera, for example, or genetic

> concordance with some agreed on standard in a genetically engineered

> ape, or genetically mis-engineered human, may lead to "demotion" as

> well as uplifing with respect to civil rights and liberties."

The first thing to ask is how human society goes about this. Your first question is "who decides?" Well, who decides in human society that humans can vote, drink booze, and apply for credit?

The state declares that if you're a citizen and you've reached the age of consent, you can vote. That's a pretty liberal and sweeping allowance. There's a general assumption of personhood; other factors, like level of education, race, gender, sexual orientation, etc., are irrelevant. So, when it comes to uplifted animals, citizenship and the right to vote can't be tied into their "species," or other superfluous characteristics that we ourselves don't invoke as reasons for not allowing a person to vote.

Regarding the booze question, again that's the state deciding in conjunction with democratically achieved consensus and a dash of social contract thrown in. And as for applying for credit, that's quite obviously up to the individual companies who are offering it. Based on what I've seen to date in terms of how credit cards are given out like candy, I'm surprised that credit card companies haven't already offered credit to bonobos and platypuses.

Your next question is about the equality of citizens. Actually, once the age of consent is achieved (and you haven't violated the social contract with anti-social behaviour), you are equal under the law regardless of your physical and psychological proclivities. We don't have tiers of citizenship in liberal democracies -- to do so would be a form of apartheid. I think it would be an extremely bad idea to start "demoting" uplifted nonhumans or psychological delayed humans based on some personhood metric. It's a binary concept - you're either an equal citizen under the law or you're not a citizen.

Ultimately, I think your question is this: at what point does an uplifted nonhuman enter the social contract? I would argue that once personhood is determined in an animal, the social contract comes into play. We cannot discriminate between animal and human societies. Nonhumans today already deserve state protection and laws to defend their interests (ergo the pending progressive citizenship legislation in Spain that would recognize the great apes) -- even though they cannot articulate their needs themselves. It's obvious when abuse happens, and it's our responsibility to look out for nonhuman interests. They are part of the social contract, but we acknowledge that their limited psychologies don't allow for other citizenship type behaviour like voting. The same policy is applied to small children and the severely disabled. There is nothing new here.

As for voting and other citizenship perks, we'll know that uplifted animals want to participate in the social and political arena when they start asking for it -- and we'll have to listen. To ignore their pleas for political inclusion, the right to vote and organize, would be discrimination and unconstitutional.

Tuesday, August 8, 2006

Metal for the masses

As most of my friends know, I'm a total metal head. I've been listening to heavy metal and other forms of extreme music since I was 13 years old. If it's loud, dark, and thrashy, I'm there. And I’ve also been known to join a mosh pit or two.

As most of my friends know, I'm a total metal head. I've been listening to heavy metal and other forms of extreme music since I was 13 years old. If it's loud, dark, and thrashy, I'm there. And I’ve also been known to join a mosh pit or two. Surprised? Even a bit disappointed? Well, you shouldn't be.

Heavy metal is a much misunderstood and maligned genre that allows for the expression of aggressive, raw and alternative forms music. It also allows for the expression of unconventional and even taboo subject matter as well. Metal often addresses social issues that other genres don't dare touch: violence and cruelty, the existence of evil, the problem of religion, the paranormal and occult, drug use, alienation, existentialism, apocalyptic visions and the horrors of war.

While often criticized as being supportive of these darker themes (which some bands undeniably are), metal acts often provide a window to the world in which the uglier elements are brought out and exposed. Some people go to horror movies or read the latest news headlines, others crank the metal.

One band that epitomizes the best and worst that heavy metal has to offer is Slayer. These guys have been around for nearly a quarter of a century and have conceded nothing in terms of their ability to churn out extreme music. Lyrically and musically, they’re everything you’d expect from a metal band—-including frequent (and often juvenille and hypocritical) references to the occult.

Thus it was with some anticipation that I picked up their latest CD. It has been 14 years since the original line-up, Tom Araya (bass guitar and vocals), Kerry King (guitars), Jeff Hanneman (guitars) and Dave Lombardo, have put out an album. And it would appear that this time around Slayer have some serious axes to grind.

Slayer has chosen to direct their ire at the two things they most love to hate: religion and war. Given the current geopolitical situation, they have lots to complain about—and there’s plenty of ugliness to unveil. Their new CD, titled “Christ Illusion,” targets the warped aspects of religion and its role as the instigator of current global conflicts.

Slayer explicitly attacks the culture war between the two competing religions, Christianity and Islam. The opening track, “Flesh Storm,” declares:

It's all just psychotic devotionAnother track, "Eyes of the Insane," engages in the subjective perspective of a soldier suffering from post traumatic stress disorder.

Manipulated with no discretion

Relentless

Warfare knows no compassion

Thrives with no evolution

Unstable minds exacerbate

Unrest in peace...only the fallen have won

Because the fallen can't run

My vision's not obscure

For war there is no cure

So here the only law

Is men killing men

For Someone else's cause...

And in the anti-religion track, “Cult,” Araya sings:

Oppression is the holy warToday, very few artists have the audacity to express their anger and frustration in this way. Perhaps it was possible back in the 1960’s with the rise of the anti-war and folk movement, but that kind of naive approach would wear thin today. We’re far too cynical and even defeatist to think about putting flowers in the nozzles of rifles.

In God I Distrust...Is war and greed the Master's plan?

The bible's where it all began

Its propaganda sells despair

And spreads the virus everywhere

Religion Is hate

Religion Is fear

Religion is war...

That’s where metal comes in. It’s cathartic, sincere and hard-line. Metal artists can thematically deal with the ravages of war and the perverseness of religion while sneering at their critics or those who would dismiss them out of hand.

It’s metal for the masses.

Monday, August 7, 2006

Good critique of SETI

A very good and concise critique of the SETI project was recently published on Space Daily. The article is largely a rebuttal to Seth Shostak's recent article, Is SETI Barking Up the Wrong Tree? (which I also critiqued a few weeks back).

A very good and concise critique of the SETI project was recently published on Space Daily. The article is largely a rebuttal to Seth Shostak's recent article, Is SETI Barking Up the Wrong Tree? (which I also critiqued a few weeks back). Excerpt:

The situation is significantly more complex: while we, for instance, think that the astrobiological revolution gives us very strong reasons to expect life and intelligence abound, this has almost nothing to do with actual practice of SETI which we believe is largely misguided (with some exceptions listed above).[As an aside, I had a pretty good laugh after I read this article. My immediate reaction was to forward a link to my cosmologist friend, Milan Cirkovic. As I was about to do so, I realized that the article was written by none other than Milan himself (along with Larry J. Klaes).]

Defenders of the SETI orthodoxy obviously-as, sadly enough, similar to many other well-documented cases in the history of science-put more weight upon the "orthodoxy" than upon the "SETI" part of the syntagm. In order for this rhetorical trick to pass below the radars, they substitute a scarecrow: whoever doubts the prospects of SETI as we do it, surely holds the pretentious and preposterous view that we are alone in the Galaxy. We strongly beg to differ.

SETI is a human endevoar, perhaps most quintessentially human of all scientific pursuits in the entire history of our species. As such, it is prone to typically human mistakes and delusions. This is clearly unavoidable. What is eminently avoidable, however, is that such mistakes and delusions are publicly defended in a dogmatic, "no-alternative" manner; especially when such mistakes and delusions are grounded in an old-fashioned, conservative and anthropocentric view of the mind and the universe.

Sunday, August 6, 2006

Louann Brizendine's Female Brain

Louann Brizendine's latest book, The Female Brain, looks very interesting. Description:

Louann Brizendine's latest book, The Female Brain, looks very interesting. Description:Every brain begins as a female brain. It only becomes male eight weeks after conception, when excess testosterone shrinks the communications center, reduces the hearing cortex, and makes the part of the brain that processes sex twice as large.

Louann Brizendine, M.D. is a pioneering neuropsychiatrist who brings together the latest findings to show how the unique structure of the female brain determines how women think, what they value, how they communicate, and who they’ll love. Brizendine reveals the neurological explanations behind why

• A woman uses about 20,000 words per day while a man uses about 7,000

• A woman remembers fights that a man insists never happened

• A teen girl is so obsessed with her looks and talking on the phone

• Thoughts about sex enter a woman’s brain once every couple of days but enter a man’s brain about once every minute

• A woman knows what people are feeling, while a man can’t spot an emotion unless somebody cries or threatens bodily harm

• A woman over 50 is more likely to initiate divorce than a man

Women will come away from this book knowing that they have a lean, mean communicating machine. Men will develop a serious case of brain envy.

Saturday, August 5, 2006

Minority Report's future visions

I watched Minority Report for the umpteenth time this evening and kept track of the various futuristic elements that were portrayed in the film.

I watched Minority Report for the umpteenth time this evening and kept track of the various futuristic elements that were portrayed in the film.Most of the ideas are quite plausible, and this is not by accident. During pre-production, Speilberg assembled a group of futurists and technologists to brain-storm the various futuristic elements that eventually made their way into the movie. According to Wikipedia:

In 1999, Spielberg invited fifteen experts convened by Global Business Network and its chairman, Peter Schwartz (and the demographer and journalist Joel Garreau) to a hotel in Santa Monica, California to brainstorm and flesh out details of a possible "future reality" for the year 2054. The experts included Stewart Brand, Peter Calthorpe, Douglas Coupland, Neil Gershenfeld, biomedical researcher Shaun Jones, Jaron Lanier, and former MIT architecture dean William J. Mitchell. While the discussions didn't change key elements needed for the film's action sequences, they were influential in introducing some of the more utopian aspects of the film, though John Underkoffler, the science and technology advisor for the film, described the film as "much grayer and more ambiguous" than what we envisioned in 1999.My list includes:

- murder precognition (ie the ability to predict murders by converting human brains into 'pattern filtering devices')

- murder precognition (ie the ability to predict murders by converting human brains into 'pattern filtering devices')- holographic and fully interactive user interfaces

- genetically modified flora (including modifications like poison and mobility)

- immersive virtual reality

- self driving automobiles and smart roads (including roads that allow cars to traverse the walls of buildings)

- automobile lock-down (eg so police can seize control of an automobile)

- mag-lev vehicles (magnetic levitation)

- flying troop carriers

- retinal eye scanners

- robots endowed with AI, surveillance robots (eg robotic 'spyders' that perform search-and-scan sweeps, can problem solve and communicate with each other)

- fully automated factories (eg a car assembly plant)

- smart materials with the capacity for animated graphic display (eg cereal boxes with cartoons on them and scrolling headlines on magazine covers)

- tailored narcotics (eg. recreational drugs for "the educated")

- targetted advertising, holographic advertising ("Hey John Anderton, you could use a Guinness")

- holographic projection devices with removable media

- detention centres in which prisoners are in stasis but are fed a stream of images and experiences (grossly unethical and something I should blog about)

- non-lethal weapons, including sick-sticks (causing the person on the receiving end to projectile vomit), neural paralyzer (ie brain-cuffs) and audio guns (low frequency audio projectile weapons)

- hoverpacks(ie the 'ol rocket-pack idea)

- mention of molecular nanotechnology (a newspaper headline)

- eye transplants

Let me know if I missed any!

Tuesday, August 1, 2006

World Future Society conference review

I was at the annual World Future Society conference this weekend manning a table for the World Transhumanist Association. The theme of this year’s conference was “Creating Global Strategies for Humanity’s Future.” Key speakers included Ray Kurzweil, Joel Garreau and Walter Truett Anderson.

I was at the annual World Future Society conference this weekend manning a table for the World Transhumanist Association. The theme of this year’s conference was “Creating Global Strategies for Humanity’s Future.” Key speakers included Ray Kurzweil, Joel Garreau and Walter Truett Anderson. At our table I had a number of WTA brochures, including literature promoting the WTA’s annual TransVision conference which will be held at Helsinki from August 17-19. I also brought along literature promoting the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies, Betterhumans, and local groups like the Toronto Secular Alliance. I was also fortunate to have the assistance of a couple local volunteers. I was hoping to do some live blogging, but the WiFi connection at the hotel was utterly inadequate and virtually non-existent.

The WFS conference, which boasted upwards of 1,000 attendees, was held at the Sheraton Centre in downtown Toronto. At any given time during the 3-day conference there were 5-10 presentations running simultaneously, with topics touching upon such themes as business and careers, future methodology, resources and the environment, technology and science, and values and spirituality. There were a number of table-top displays in addition to our own, including other futurist groups and new age style religions. There were also a number of students at the conference, including a very friendly and enthusiastic group from Venezuela [thanks for hanging out with us, guys].

Having never been to a WFS event before, I wasn’t sure what to expect—particularly from the perspective of an exhibitor. While the conference theme was largely about “humanity’s future,” my sense going into the conference was that the WFS crowd would be more conservatively minded and more focused on near-term and business related issues.

For the most part this proved to be largely true, but overall I’d have to say I was impressed with the futurists at the conference. Terms that echoed in the conference rooms included the usual suspects: AI, nano, MEMS, virtual reality, and cybernetics. For this particular audience, most of whom were interested in corporate futurism, the idea of ‘enhancing’ human capacities was a given. I got the sense from several attendees that the ‘transhumanism’ moniker wasn’t completely necessary.